Revolutionary Soldier

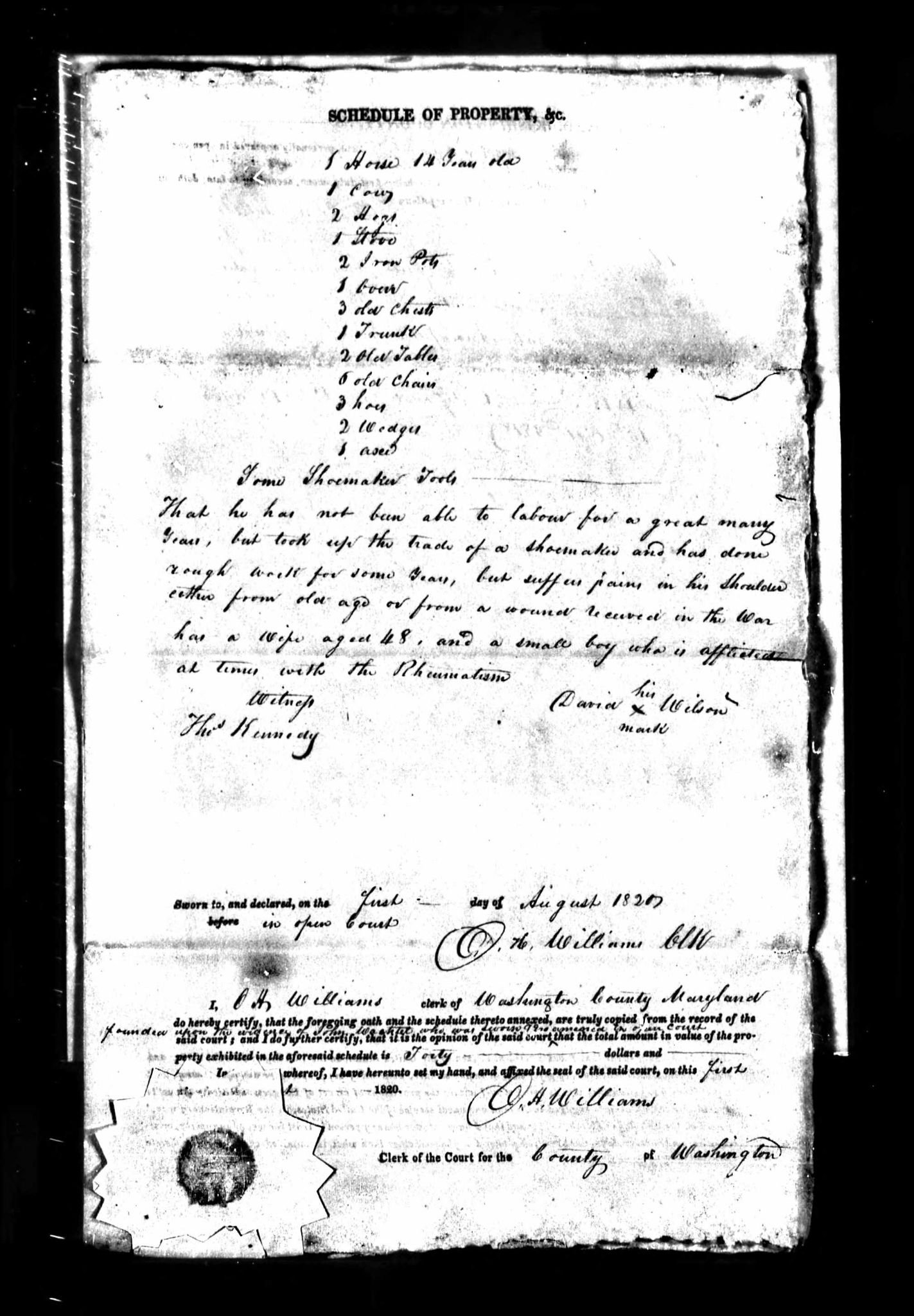

This page from a veteran’s pension application shows the participation of African Americans in the Revolutionary War. Filed in 1818 by David Wilson, a free Black man from Chestertown, Maryland, these papers contain testimony of his military service forty years earlier. He was able to claim modest financial compensation for his service thanks to an act of Congress making such funds available to all Revolutionary veterans. Wilson was one of only three Black men from Kent County known to have served in the Continental Army during the Revolution, but his case was not unique. It is thought that about 9,000 Black soldiers served in the Continental Army during the war, and though they made up a small fraction of the roughly 200,000 soldiers known to have fought, they served for significantly longer periods of time, on average eight times longer than their white counterparts.

Included in the application is supporting testimony from two fellow Maryland servicemen, one of whom writes that Wilson “enlisted himself” in the 5th Maryland Regiment at Chestertown in the summer of 1778, indicating that he was a free man who chose to join the fight for independence. Many other Black soldiers were slaves forced to fight as substitutes for their white owners n the Eastern Shore, who by 1780 were being forced into military service as substitutes for their white masters, David Wilson voluntarily elected to join the army, at a period when the outcome of the war was far from certain. He would experience much of that uncertainty firsthand. Wilson fought in almost all of the most significant battles of the Southern campaign, receiving a life-long shoulder wound in the process. From the massacre of American soldiers at Camden, to the victory at Cowpens, he tied his fate to the Continental Army for five brutal years until peace returned in 1783. David Wilson himself signed on for a three-year term of service and chose to remain for the duration of the conflict, while many white soldiers in his regiment enlisted for only a year. At the Siege of Yorktown in late 1781, allied French officers observed that roughly one in four American soldiers present on the field was Black.

By the time he compiled his pension application in 1818, he was living in Washington County, Maryland, perhaps on a tract of land granted to him as a Revolutionary War veteran. Despite already being legally free, his home of Kent County remained a slave economy with a sharp racial divide. The army gave him the promise of steady wages, land bounties, and perhaps even some form of equality within the strict military hierarchy than he otherwise would have received in the civilian life of Kent County. Like many other African American soldiers, military service helped Wilson to level the playing field. He was able to achieve economic independence through wages, land grants, and a veteran’s pension, while participating in the relatively egalitarian culture of the army, in which a free Black man trained as a shoemaker and a white member of Maryland’s political aristocracy could find common ground and mutual respect.

– Jack Dodsworth

Click "Four Centuries" below to return to the main page.