Abraham Robinson : The Story of Oysters, Ice Cream, and Black Success

by Braxton Berry and Alex Trabold

Figure 1. An advertisement for Abraham Robinson’s restaurant on High Street. Source: Kent News, September 14, 1907 as found in Historical Society of Kent County, “Community, Prosperity, & Resilience: African Americans in Chestertown, Maryland, 1700s to the Present,” 2022.

The story of Abraham “Abe” Robinson is that of resiliency and power in the face of Jim Crow discrimination. A Chesapeake Heartland collection of nearly 700 business invoices details Robinson’s life as a well-connected and economically active Black business owner, who despite being a generation removed from slavery and operating in a deeply racist society, cultivated an influential business in downtown Chestertown. Along with his wife Nettie, Robinson moved to Chestertown in the 1890s, and by 1907, they opened a restaurant serving oysters and ice cream (Figure 1).

The research we have generated through his business records adds to Abe Robinson’s portrait. Albeit limited to a series of receipts, our findings reveal Robinson’s extraordinary business dealings as well as his impact on Kent County and the greater Chesapeake Bay Region.

Robinson was not only a Black business owner, but also served Chestertown as a civic and spiritual leader. From articles in the Baltimore Afro-American, we know that Robinson was an active church leader, involved in a fraternal organization, had extensive connections in the Chesapeake Region, and was well-connected to Baltimore society. Robinson was a Reverend, frequenting Janes M.E. Church, where he would preach “interesting and inspiring sermon[s].” He also visited Bethel A.M.E. Church, where he made “short addresses” to support the work of the Delphi Court of Calanthe—a fraternal benefit society for African American women. His family would often visit Baltimore, including his son and wife. On one occasion, his wife traveled to Baltimore in order to check into Mercy Hospital for an unspecified medical operation. While we’re sure it wasn’t a trip Nettie or Abe wanted to make, their ability to travel to Baltimore for medical treatment suggests their economic and social wherewithal. It also might suggest that sound medical treatment for African Americans in Kent County was hard to access.

Robinson had a broad economic reach across the Eastern Coast of the United States. He received large shipments of food and other products from across the Mid-Atlantic via numerous railroad shipping companies. Robinson’s receipt collection details almost daily shipments of ice, peaches, sugar, oysters, cigars, and beverages from locations ranging from Virginia to Pennsylvania (Figure 2). Robinson also invested in kitchen appliances, as well as making regular coal, water, gas, and electricity payments to keep his business running. Many of his invoices come via shipment companies, such as the Maryland Virginia and Delaware railway, which operated from 1883 until it was bought out by the Pennsylvania Railroad in July 1919. Robinson continued to patronize the railway even after its buyout (Figure 3).

Figure 2. A September 22, 1915 receipt for several packages of oysters, peaches, and ice cream cones.

Figure 3. Map of the Maryland, Virginia, & Delaware Railway.

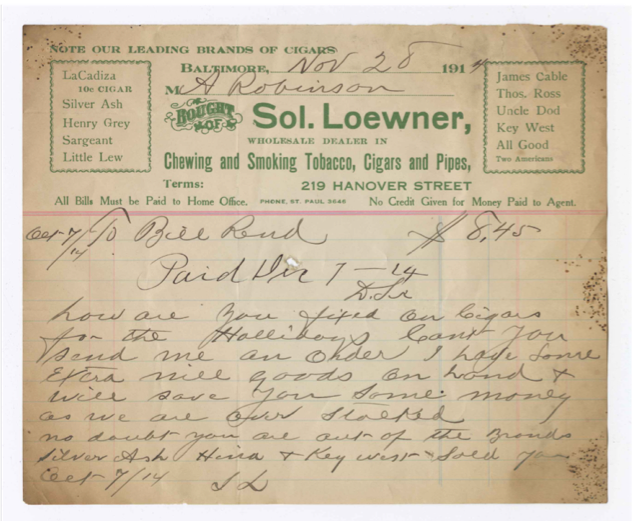

Robinson also cultivated relationships with more local grocers, tradesmen, and vendors. Oftentimes, Robinson’s vendors of choice were white. Herman Blackway, his bottle supplier, and William Deiches, one of Robinson’s tobacco vendors, were both white. Examples of friendly, personalized correspondence exist within his receipts, suggesting that Robinson was well known and respected by other business owners. For example, in a letter to Robinson Sol Loewner, a Baltimore Tobacco dealer, makes Robinson a quality guaranteed offer for Cigars during the holiday season; “How are you fixed on Cigars for the holidays? Can’t you send me an order I have some Extra…goods on hand & will save you some money as we are over stocked.” (Figure 4).

Robinson accumulated a considerable amount of purchasing power, spending large sums of money to run his Oyster bar and ice cream shop, known as the Evening Glory between 1910 and 1919. During just one month in November 1915, Robinson spent a total of $19.82 just on shipping costs for oysters, around $600 in today’s money. Robinson often spent large amounts of money on single purchases. In September 1915, for example, he purchased nearly 6,000 lbs. of ice (Figure 5). Robinson also spent a similarly large sum in November 1915 when he bought $375.45 worth of cigars (inflation adjusted).

While our research was incredibly revealing and rewarding, we have only scratched the surface of what’s still to be uncovered in this receipt collection. The study of Abraham Robinson’s life requires much more extensive research, which as we graduate from Washington College, we urge future students to take on. While many more insights can be mined from Robinson’s receipts, we already know that this remarkable business owner made significant contributions to his community. Robinson’s life is a tale of a man who had considerable economic reach, was intimately connected with prominent members of the local community and surrounding region and defied the norms of the time to occupy a place of prominence in Jim Crow-era Chestertown.

Works Cited

Baltimore Afro-American, Dec. 27, 1913, 8.

Baltimore Afro-American, Apr. 1, 1916, 3.

Baltimore Afro-American, Oct. 27, 1917.

The Evening Journal, July 23, 1919, 3.

Historical Society of Kent County, Community, Prosperity, & Resilience: African Americans in Chestertown, Maryland, 1700s to the Present, 2022.