Goin’ Back to the Old Ways: Chesapeake Narratives on African American Traditions by Queen Cornish

Over the course of one month, I had the pleasure of interviewing three narrators: David Cornish Sr., Hess Love, and Airlee Ringgold-Johnson. All interviews were conducted virtually to mitigate the risk of COVID-19. The goal of this oral history project was to investigate how the Chesapeake Bay has shaped the cultural traditions of African Americans, both past and present. Furthermore, I examined the intersections between the region’s natural resource extraction, traditional foodways, and diverse spiritual practices using Julian Steward’s Cultural Ecology framework. Steward’s methodology was to document resource extraction from the environment, identify patterns of human behavior, and assess how these patterns influenced cultural practices. In essence, cultural ecology represents the “ways in which culture change is induced by adaptation to the environment” (Steward, 1955). The commonality between each narrator was their personal relationship with the bay’s waterways and the recognition of their family legacies.

Oral History Interview with David Cornish, Sr. on July 23, 2022

He/Him, 59 years old, Minister, Cambridge, Maryland

“So, I come from a family that cooks, anything we can catch outside.”

Cornish was born and raised on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. During his formative years, Cornish traveled back and forth between Cambridge, Maryland and Wilmington, Delaware, where he now resides.

In the Cornish household, the kitchen was both the center of storytelling and life lessons. “[I] come from a big family,” said Cornish. “During those times I had eleven brothers [and] four sisters. And we learned how to stick together. We learned what unity was; one eat, we all eat.” He witnessed his mother and father cooking for one another. If his mother was too exhausted to cook, then his father would step in and cook for everyone. This display of love inspired Cornish to do the same for his wife, where responsibilities were shared. The family would gather around and enjoy the flavors of fried catfish, hoe cakes, corn fritters, and sauteed poke greens foraged from the backyard.

Coming from a long line of land stewards, his father and older brothers harvested cucumbers, beans, watermelons, and tomatoes. When it grew colder, their labor switched from agriculture to the maritime industry. His father shucked oysters and pushed an 140lb wheelbarrow of them day in and day out.

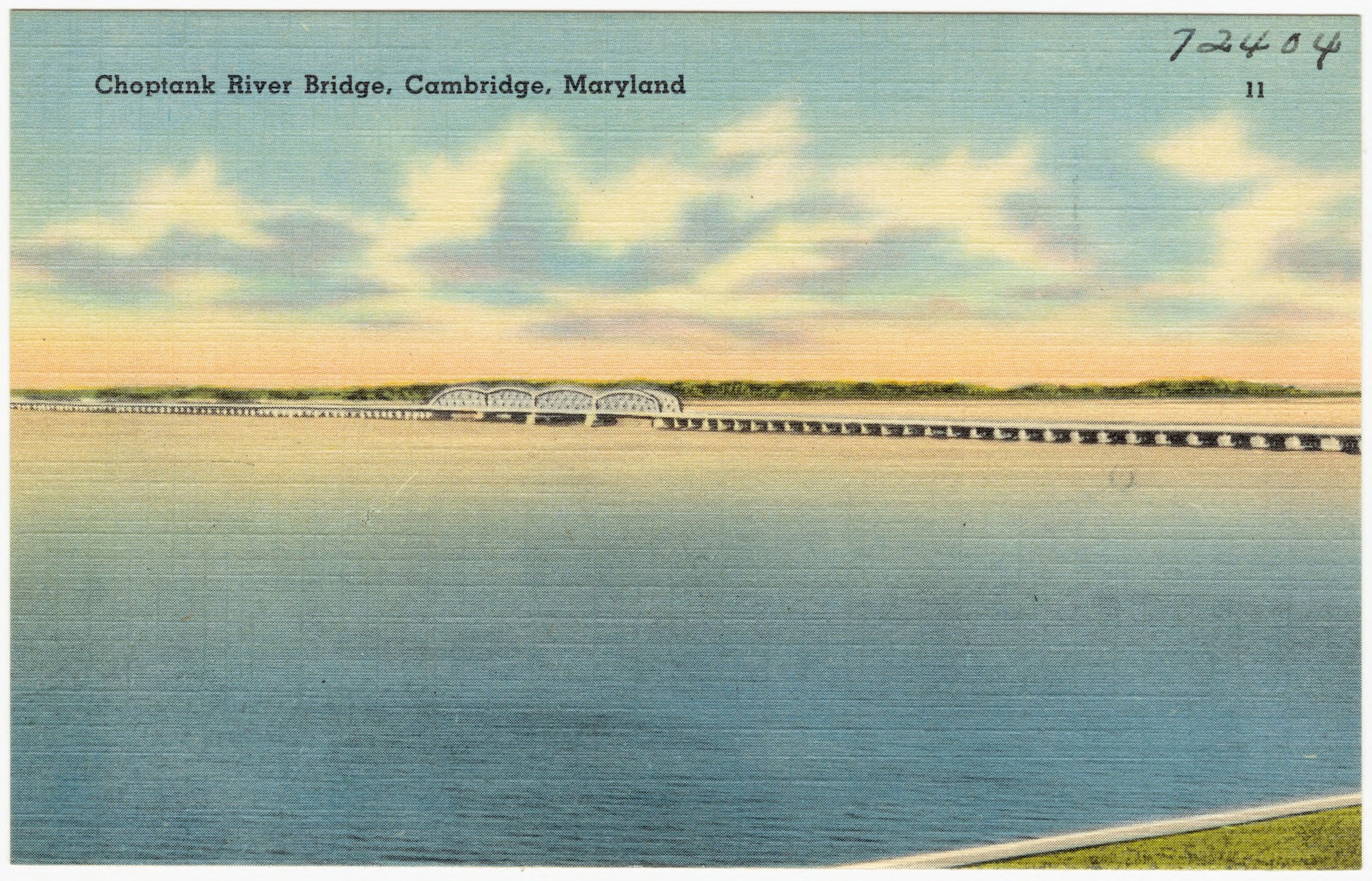

As a young boy, Cornish was baptized by his father, Bishop Clarence Cornish Sr., in the Choptank River.

Submerged beneath those freezing waters, Cornish had accepted his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. From what he remembers, the Choptank River was one of the few places where African Americans could be baptized, since most churches did not have baptism pools during those times. Despite that cold winter’s day, his relationship with the water was so strong that he would pass out by the sight of it. The waves would hypnotize him as he watched them come in and out.

He has seen many waterways, but none have compared to the spirit of the Choptank River – and the energy it possesses.

Someday, he hopes to return to the shore once it’s ready to receive and embrace him. By that time, he’d be ready to embrace it.

Oral History Interview with Hess Love on July 24, 2022

She/Her, They/Them, 33 years old, Hoodoo Scholar and Writer, Annapolis, Maryland

“It’s a lot of us from Annapolis that come from watermen. People who were fishers and crabbers, got oysters and all types of stuff. That our families, you know, spiritually, baptisms would happen in the water.”

Love grew up near the Severn River, where swimming was a must for riverside communities. The river provided sanctuary for oysters, blue crabs, and a space for cultural and recreational activities.

USGS Topo View, (HTMC, 1948 ed.), Baltimore, MD, Severn River

Amidst the passing of their grandmother back in 2010, Hoodoo became a sacred space to process their grief and love. Love states, “[my grandmother] taught me how to do certain things with them [plants and herbs]. And I didn't know that was rootwork and I didn't understand there was a term [for it] until, like I started intentionally researching like the Black spiritual traditions of people here.” This led her to making connections between her ancestral practices and Chesapeake Hoodoo (also known as Tidewater Hoodoo). According to the Chesapeake Conjure Society, “Hoodoo is a tradition, a generational heirloom that is simultaneously medicine, magic, and religion…Hoodoo is a system of survival, adaptation, resistance and reclamation.”

Love’s spiritual practice of Hoodoo is centered around the Chesapeake Bay’s cultural landscapes. The National Park Service defines cultural landscapes as “historically significant places that show evidence of human interaction with the physical environment.” (NPS, n.d). Love recognizes the interconnectedness between the natural environment and the survival of her ancestors. The Bay and its landscapes act as a refuge for native plant species, fowl, and many land animals. African Americans continue to use the natural environment to divine, foster community, engage in protection work, and to preserve their rich, cultural heritage.

Love’s study and reclamation of Hoodoo has encouraged them to go back to their whimsical self as a child. The land, and its trees, shelters and holds space for them. These interactions have inspired them to learn how to love, specifically how to better love Black people.

Oral History Interview with Airlee Ringgold-Johnson on August 2, 2022 She/Her, 74 years old, Community Historian, Chestertown, Maryland

“Don’t worry about anything; instead, pray about everything.”

As a young girl, Johnson had limited access to the Bay’s waterways. In Kent County, Maryland, African Americans were not allowed at public beaches, except for one day out of the year. The day after Labor Day, they were able to access Tolchester Beach, which was an amusement park. In Anne Arundel County, there were two beaches just for African Americans: Carr’s Beach and Sparrow’s Beach. During the summer, the Ringgold family would make annual visits to these beaches.

After Labor Day, there was also an annual boat ride just for African Americans. This excursion boat traveled from Betterton Beach to Baltimore and Annapolis. It offered different amenities such as a live band, a restaurant, and a bar. It was one of the few sources of entertainment on the water.

On this special day, African Americans were allowed to sit anywhere on the boat. However, they were restricted to the lower levels once it resumed to daily ferries for the general public.

Throughout her life, Johnson has fallen in love with the water due to its calming nature. Yet, she did not learn how to swim until the age of 21.

Johnson began rowing at the age of 55 and continued for the next 15 years. Her appreciation for the water is supported by her spirituality. Before work, she starts her day meditating and praying to God. The quiet allows her to seek guidance and to honor their covenant.

Historic American Buildings Survey, C., Pickering, E. H., photographer. (1933) Old Custom House

Johnson currently works as a Community Historian for the Starr Center’s Chesapeake Heartland Project. The Starr Center is located within the Custom House; formerly owned by the enslaver, Thomas Ringgold.

Despite sharing the same last name as him, Johnson feels the support of her ancestors as she walks towards her office. She states, “I just feel like as I walked through the house, I feel like my ancestors have — they’re cheering me on. You know, I think it’s almost like I feel the pride of just being there actually.”

She is enlisting the help of other Chestertown residents to share their family histories. In addition, she’s been encouraging her friends to return to Chestertown. From the Civil Rights Movement to working on the Chesapeake Heartland Project, Johnson has continued to make her ancestors proud. Every day when she goes to work, the Chester River is a reminder of who she is and whom she comes from.

Where it All Started

The tide of the Chester River creeped closer and closer to my feet, till eventually, it arrived beneath the soles of my shoes. I sat on the bench in deep contemplation, watching the waves move back and forth. I inherited my love for the water from my father, David Cornish Sr., who I had the honor of interviewing. We’ve been researching our family traditions on the Eastern Shore, and I thought, “why not turn this into a project?”

This project has allowed me to re-remember whose I am, which not only includes my ancestors but also the water. The Chesapeake Bay, the Choptank River, and the Chester River have all contributed to my protection and success as a scholar. Without them, my work would lose its roots and as a result, I would lose myself. I give thanks to these waters for sustaining me and my lineage; for nurturing us back to health; for guiding us down the shore; and for reminding us that we are not alone. Though no one was around when I took this photo, the waters kept me company and revealed what I have always known: this is what home feels like.

Personal Collection, Cornish, Queen, photographer. (2022) Chester River near Custom House

Works Cited

Choptank River Bridge, Cambridge, Maryland [Card]. ([ca. 1930–1945]). Retrieved from https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/w9505620m

Cultural Landscapes (U.S. National Park Service). (n.d.). Www.nps.gov. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/culturallandscapes/index.htm

Historic American Buildings Survey, C., Pickering, E. H., photographer. (1933) Old Custom House, 101-103 Water Street, Chestertown, Kent County, MD. Chestertown Maryland Kent County, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/md0289/.

Johnson, A. R. (1953). Chesapeake Heartland : Still Image : Ringgold family swimming at the beach, 1953 [CH_CA_2020_SC_021_024]. Archive.chesapeakeheartland.org.

https://archive.chesapeakeheartland.org/Detail/objects/231

Julian Steward. (1955). Theory of Culture Change : The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution.

What is Hoodoo. (n.d.). Hoodoo Society. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from https://hoodoosociety.com/hoodoo